On July 8, 2025, the Bombay High Court delivered a ruling that reignited a long standing but under discussed issue in India’s caste based reservation system. A student, born to a Scheduled Caste (SC) mother and an upper caste father, approached the court seeking a caste certificate to avail SC category benefits. The court denied his request. Why? Because caste, as per legal precedent, follows the father.

- Two Marriages, Two Outcomes

- Legal Justification and Its Flaws

- 1. It Presumes Caste is Cultural, Not Structural

- 2. It Reinforces Patriarchy Under the Guise of Objectivity

- Silent Disempowerment of Dalit Women

- Encouraging One Kind of Inter Caste Marriage

- Why It Matters Today

- What Needs to Change?

- Final Word

- Summary

This ruling doesn’t stand alone. It echoes decades of judicial interpretation that consistently enforces a patriarchal standard in determining caste identity. And in doing so, it lays bare a structural flaw the Indian caste benefit system is not just casteist, it is deeply patriarchal.

Two Marriages, Two Outcomes

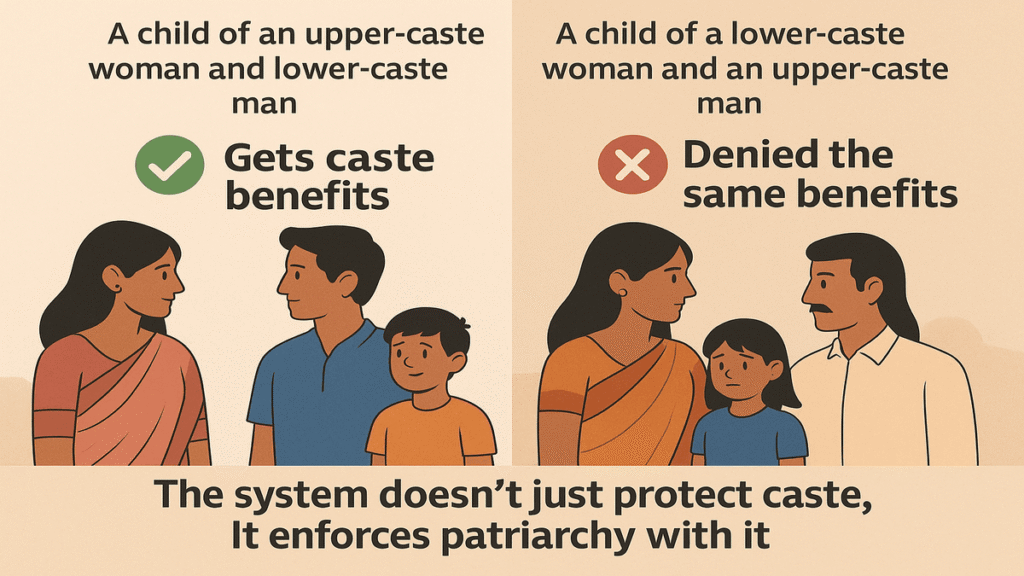

Consider two hypothetical inter caste marriages:

1. Upper caste woman + SC man → Their child gets caste benefits.

2. SC woman + Upper caste man → Their child is usually denied the same benefits.

This isn’t just a technical glitch or legal inconsistency it is systemic bias. The courts presume that caste is inherited patrilineally, just like in a traditional Brahmanical order. If your father belongs to a reserved category, you’re in. If your mother does, you’re out unless you prove that you were raised in SC/ST conditions and faced discrimination accordingly.

Essentially, the mother’s identity is conditional. Her experience of caste-based oppression does not automatically translate to her children unless it’s validated through evidence of continued suffering. The father’s caste, however, is taken as absolute.

Legal Justification and Its Flaws

The Bombay HC, like previous courts, relied on Supreme Court judgments (like V.V. Giri vs D. Suri Dora, 1960s and reaffirmed in Rameshbhai Dabhai Naika vs State of Gujarat, 2012), which state that caste identity for the purpose of reservation depends not just on birth but on the environment in which a child is brought up.

But this seemingly neutral standard hides two major flaws:

1. It Presumes Caste is Cultural, Not Structural

According to this view, if a child of an SC mother is raised in an “upper-caste” household, they do not face caste discrimination, so they shouldn’t get benefits. But this ignores structural inequity. Caste isn’t merely about personal experience it’s about generational access (or denial) to power, opportunity, and dignity.

A woman who is Dalit doesn’t suddenly shed her identity or her trauma when she marries outside her caste. Yet her children are expected to inherit nothing of her struggle?

2. It Reinforces Patriarchy Under the Guise of Objectivity

By holding the father’s caste as the default, courts implicitly state that only men pass on social identity. This mirrors the Manusmriti logic where women are defined by their fathers, then husbands, and then sons. In 2025, Indian courts are still upholding that legacy, albeit wrapped in modern legalese.

Silent Disempowerment of Dalit Women

This system doesn’t just fail individuals it systematically erases the agency of Dalit women. When a Dalit woman marries outside her caste, she’s not just stepping outside the boundary of her community she’s also risking the rights of her future children.

In effect, the state tells her:

“Your caste only matters when you’re suffering. If you dare to rise above it by marrying outside your caste or improving your socio-economic status your identity and your children’s entitlements are revoked.”

This is nothing less than a punishment for mobility.

Encouraging One Kind of Inter Caste Marriage

If we follow the logic to its conclusion, the system:

- Rewards upper caste women marrying lower caste men (child gets SC status).

- Punishes lower caste women marrying upper caste men (child is denied SC status).

This creates an uncomfortable truth: our caste benefit framework subtly encourages caste mixing only when it does not threaten upper caste male privilege. It’s acceptable for the caste “status” to go down from the father but not up from the mother.

This is not accidental. It’s the result of a patriarchal social contract that still governs caste transmission.

Why It Matters Today

In an age where India claims to be empowering women, uplifting Dalits, and breaking caste boundaries, this discriminatory rulebook sends the opposite message. It tells lower-caste women:

- Your caste trauma is only valid if you stay within your margins.

- Your children only count as Dalit if a man says so.

- Your upward mobility comes at a price the denial of recognition for your struggle.

What Needs to Change?

1. Amend the rule of patrilineal caste inheritance.

Caste identity should reflect either parent’s background, especially when the child is raised in that cultural and social context.

2. Acknowledge intersectional discrimination. Courts and caste scrutiny committees must factor in both caste and gender dynamics, not just legal lineage.

3. Strengthen women’s agency in caste certification.

If the mother is from a reserved category, her children should not have to jump through hoops to prove their eligibility.

4. End the conditional logic of suffering. Access to justice and opportunity should not require proof of pain. It should recognize historic injustice, even when someone is trying to escape it.

Final Word

When a child of a Scheduled Caste mother is denied caste benefits simply because the father is from a dominant caste, it’s not just a legal error. It’s a social injustice wrapped in legal formalism.

The caste system is bad enough. But when the state reinforces it through patriarchy, it doesn’t just fail the Constitution it betrays it.

Summary

This article examines a recent Bombay High Court ruling where a student born to a Scheduled Caste (SC) mother and an upper caste father was denied a caste certificate. The case reveals a deep-rooted legal bias where caste identity is inherited through the father, not the mother. It highlights how India’s caste benefit system upholds patriarchal norms granting reservation benefits to children of SC fathers but often denying them to children of SC mothers. The piece critically explores the implications of this double standard and calls for urgent reform to ensure gender equal caste justice.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of The News Drill. The analysis is based on available legal precedents, news reports, and societal observations, and is intended for informational and editorial purposes only. Readers are encouraged to independently verify legal interpretations or consult legal experts for specific concerns. The News Drill upholds freedom of expression and aims to foster informed debate on complex issues of caste, gender, and social justice in India.

Stay connected with The News Drill for in depth stories at the intersection of law, caste, and gender. Stay informed. Stay updated. Stay Ahead.

Contact: contact@thenewsdrill.com

Submit a tip or story: editor@thenewsdrill.com or visit our Contributor Page