When Madhya Pradesh’s government filed a detailed affidavit in the Supreme Court — including a chapter on the Varna system and its impact on backward classes — it signalled that the state is treating the 27 % OBC reservation issue not merely as a policy question but as a constitutional and historical contest. The affidavit extracts (such as the one you provided) became a visible piece of the legal argument: they show how the BJP state administration is trying to ground its justification for expanded OBC reservation in long standing patterns of structural disadvantage.

But the real test before the Supreme Court is legal doctrine, precedent and empirical evidence. Below is a fuller explanation of the background, arguments, procedural twists, and stakes.

Background of the case: From 14% to 27%

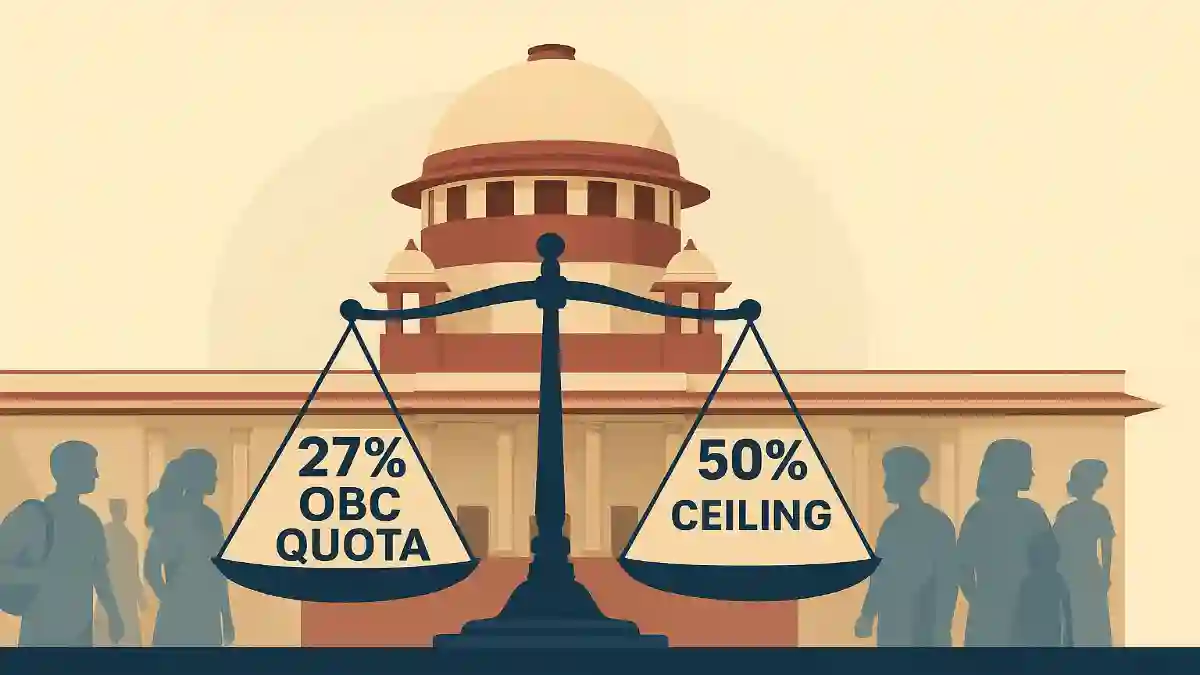

1. Original reservation structure: Historically, Madhya Pradesh (like many states) allocated 14 % reservation for OBCs, 16 % for Scheduled Castes (SC), and 20 % for Scheduled Tribes (ST). That totaled 50 % — the conventional upper limit recognized by the Supreme Court.

2. The 2019 change: In March 2019, the Kamal Nath Congress government issued an ordinance and then passed a law to increase OBC reservation from 14% to 27%. That means an extra 13%. This change was contested in court, particularly because critics argued the total reservation would breach the 50% “ceiling.”

3. Stay and judicial challenges: The High Court of Madhya Pradesh issued a stay on implementing the increased 13% in many recruitments, particularly after a challenge by a medical student regarding postgraduate seats. Because of the stay, many recruitment drives have proceeded only under the old OBC quota (14%), and about 13% of posts meant under the new quota have been kept “on hold.”

4. Total quota debate — 63% vs 73%: Much of the controversy is over whether the additional OBC quota, when combined with SC, ST and EWS quotas, breaches the permissible limit.If one counts just SC + ST + OBC, the total becomes 63%.

If one also counts 10% EWS (Economically Weaker Section), some political discourse says it goes to 73 %.The difference is not trivial for legal arguments: courts will carefully examine which quotas can be aggregated, whether EWS is independent, and what precedents say.

The Affidavit Strategy: History, Disadvantage, Remedy

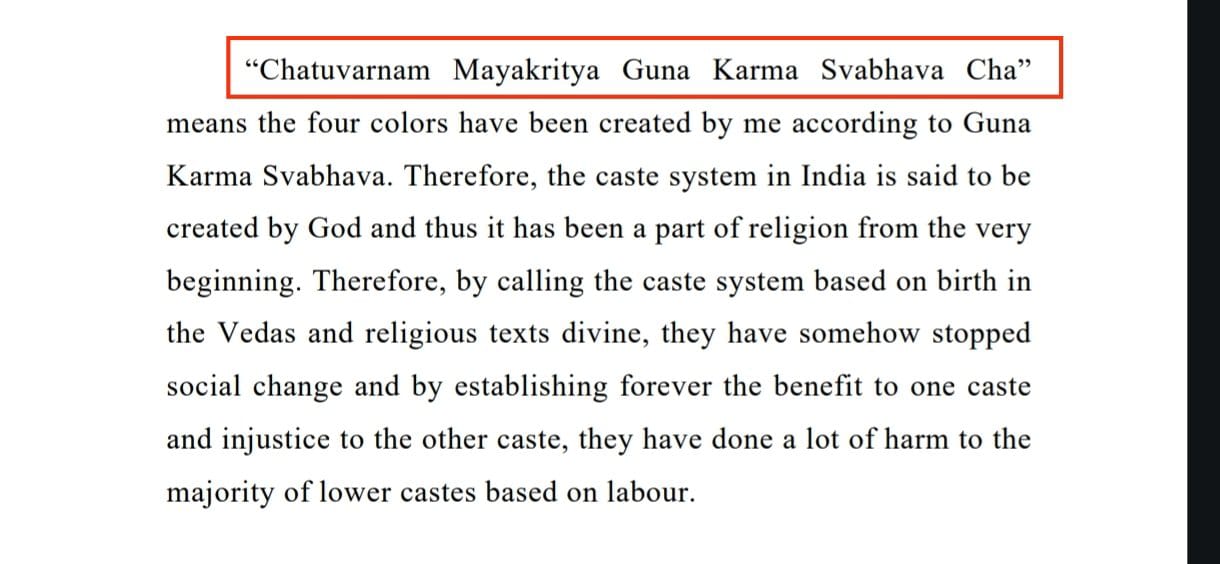

The chapter in PDF file (Chapter 4, Varna system and its impact on backward classes) is not a standalone essay — it is part of the state’s formal answer to the petitioners in the Supreme Court. The state uses it to argue that reservation is not a new or arbitrary idea; rather, it is a remedial measure in response to centuries of structural exclusion rooted in caste.

Key roles played by the affidavit:

Historical framing: The affidavit tries to show how ancient and medieval texts (e.g. Smritis, commentaries) imposed disabilities on Shudras and non-upper castes — denying education, imposing servitude, enforcing social segregation. This is used to argue that modern inequalities are not random but built over generations.

Moral-constitutional bridge: By linking historical injustice to present inequality, the affidavit attempts to bridge moral reasoning and constitutional obligations. It is an effort to persuade justices that the 27% quota is a proportionate response.

Supporting “extraordinary circumstances”: The Supreme Court’s precedents (especially when reservation exceeds 50%) demand proof of “extraordinary circumstances” or special justification. The historical narrative becomes part of that justificatory burden.

However, the court will not only look at history: it will also demand data, comparative indicators (representation, backwardness indices, public employment distribution) and evidence of continuing disadvantage.

Legal and Constitutional Constraints

1. The 50 % ceiling principle: A landmark case, Indra Sawhney v. Union of India (1992), held that reservation beyond 50 % can be permitted only in “exceptional” or “extraordinary” situations. The court also introduced the concept of “creamy layer” (excluding better-off among OBCs from benefits).

2. Precedents on exceeding 50%: Courts have sometimes allowed breaches of 50% where there is compelling data that special measures are needed. But such decisions are rare and hinge on rigorous empirical justification.

3. Burden of proof: The state must show that the 27% addition is necessary, proportionate, and addresses concrete continuing disadvantage (not just theoretical). Courts will examine whether OBCs are underrepresented in government jobs, whether the uplift is feasible administratively, and whether variation across districts or castes is considered.

4. Procedural compliance: Even if substantive merit exists, courts will check if the state followed rules: proper notifications, amendments to service rules, reservation of vacant posts, timely execution. If the state failed in procedure (for example, keeping 13% of posts on hold over years), that weakens its case.

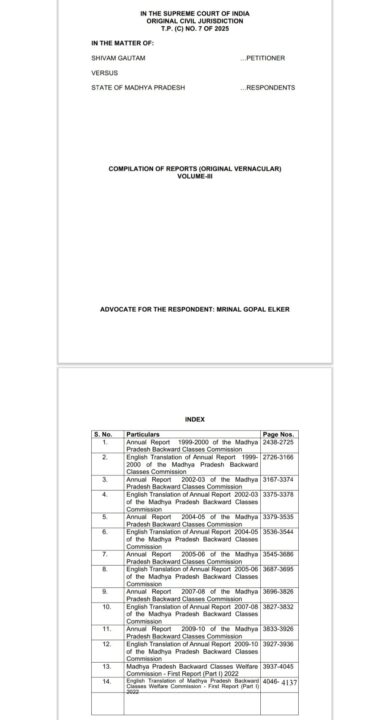

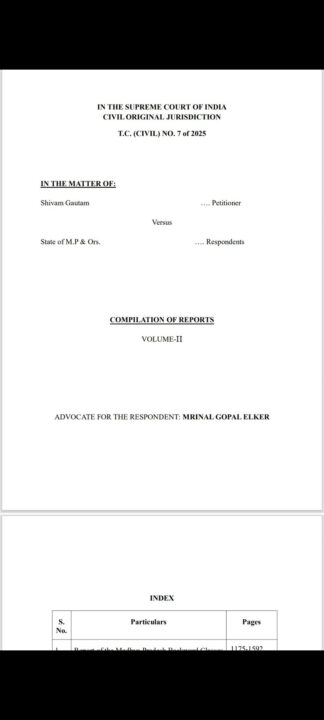

Current phase (2025): The matter reached final hearing status on the Supreme Court board, with multiple parties (state, OBC bodies, opponents) filing affidavits and arguments. Reporting in 2025 shows hearings scheduled around late September and intense political mobilisation in MP.

Click on above Download button to download full details of the case & Annexure.

Read more: Madhya Pradesh CM Mohan Yadav meets SG Tushar Mehta

Full Document in English of Shivam Gautam vs State of MP and others case is given below 👇 and by clicking on download button you can download document.