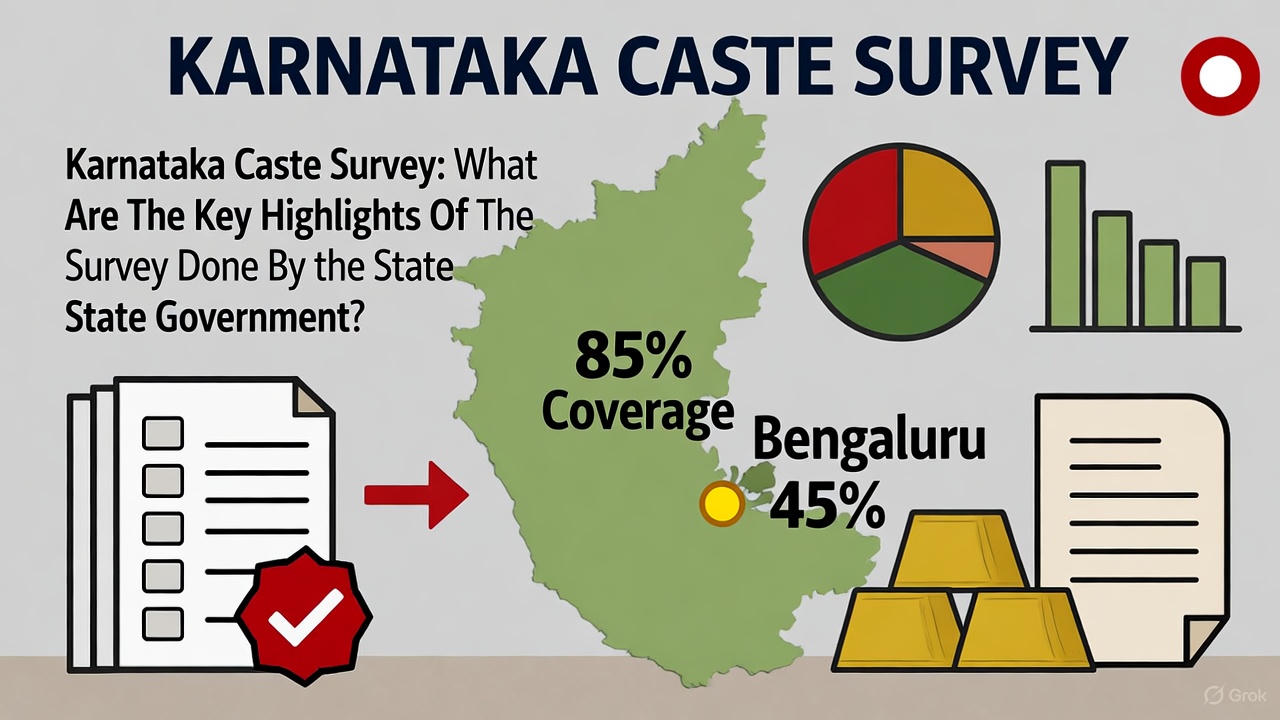

The Karnataka Social and Educational Survey, often referred to as the “caste census,” has wrapped up its fieldwork amid widespread controversy, achieving approximately 85% statewide coverage while lagging at just 45% in Bengaluru. Conducted by the Karnataka State Commission for Backward Classes (KSCBC) under the Congress-led government, the survey aims to gather data on caste, sub-caste, education, occupation, income, and assets to inform welfare policies and reservations for marginalized groups. However, critics argue it could pave the way for wealth redistribution measures, invoking Articles 39(b) and 39(c) of the Indian Constitution, which emphasize equitable distribution of resources and prevention of wealth concentration.

The survey, which cost an estimated ₹420-625 crore and involved around 1.75 lakh enumerators (mostly teachers), began on September 22 and officially ended on October 18 after multiple extensions. Households that missed the in-person enumeration can submit data online until October 31, but no further fieldwork is planned. Deputy Chief Minister DK Shivakumar has urged participation, describing it as a “scientific” and voluntary exercise aimed at equity. This marks Karnataka’s second major attempt at such data collection, following the 2015 survey that was shelved due to political pressures.

Survey Details and Coverage Challenges The 60-question form probes into sensitive areas, including land ownership, property holdings, vehicles, appliances, and even gold possessions—details that have fueled privacy concerns and accusations of it being a “wealth audit.” Rural districts like Tumakuru and Mandya achieved near-100% coverage, but urban areas, particularly Bengaluru’s high-rises and gated communities, saw lower participation due to non-cooperation, access issues, and fears of data misuse. The survey cites the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act to assure confidentiality, with data intended solely for the KSCBC and not shared with the government.

High-profile refusals have highlighted these tensions. Infosys founder NR Narayana Murthy and his wife, Rajya Sabha MP Sudha Murty—both from the Brahmin community—declined participation, submitting a self-declaration stating they do not belong to any backward class and that their involvement would not aid the government. Critics like activist Shivasundar argue this sets a poor precedent, undermining the survey’s goal of assessing relative backwardness across all communities. Former KSCBC member KN Lingappa called it a “blatant disregard for backward classes,” noting that forward communities like Brahmins often benefit disproportionately from resources despite comprising only about 2.62% of the population, as per leaked 2015 data.

Legal Battles and Constitutional Scrutiny The survey has faced multiple legal challenges. The Karnataka High Court, in response to petitions from dominant caste groups and BJP proxies, issued notices to the state and central governments questioning its constitutional validity, citing potential overlaps with Union census powers under Entry 69 of the Seventh Schedule. However, the court declined to stay the exercise, affirming states’ rights to identify backward classes post the 105th Constitutional Amendment (2021), which restored such powers after the 102nd Amendment centralized them. The court ruled participation voluntary, mandating clear notifications and prohibiting coercion by enumerators.

This ruling draws from the landmark Indra Sawhney (Mandal) judgment (1992), which upheld reservations for backward classes under Article 16(4) and mandated periodic surveys of the entire population to revise backward class lists. Yet, the voluntary aspect risks incomplete data, potentially defeating the survey’s purpose.

The Article 39 Angle: Fears of Wealth Redistribution At the heart of the debate is the potential linkage to Articles 39(b) and 39(c) of the Directive Principles of State Policy. Article 39(b) directs the state to ensure “ownership and control of the material resources of the community are so distributed as best to subserve the common good,” while Article 39(c) aims to prevent “concentration of wealth and means of production to the common detriment.” These non-justiciable principles have been invoked in past policies like land reforms and nationalization.

Critics, including BJP leaders and anti-reservation voices on social media, fear the survey’s asset-related questions could inform redistribution policies. They point to Congress leader Rahul Gandhi’s 2024 election promises of a nationwide caste census followed by a “financial and institutional survey” to redistribute wealth, jobs, and welfare based on population shares of SCs, STs, OBCs, and minorities (estimated at 90% of India). Gandhi has reiterated this in 2025, criticizing merit systems as favoring upper castes and linking caste censuses to equitable resource allocation. The Congress manifesto pledges policy changes to address wealth inequality, echoing Article 39.

A recent Supreme Court ruling (November 2024) clarified that not all private properties qualify as “material resources of the community” under Article 39(b), limiting state seizure for redistribution. Legal experts argue this tempers fears, but in Karnataka, BJP propaganda claims the survey divides castes to weaken dominant groups like Lingayats and Vokkaligas, potentially leading to sub-classification and “nationalization” of assets. The party, which supported the 105th Amendment, now hypocritically argues states lack authority.

Supporters, including the Congress government, frame the survey as fulfilling constitutional duties for social justice under Articles 15 and 16, not redistribution per se. It could reveal disparities, justifying targeted welfare without directly invoking Article 39.

Political Ramifications and Internal Tensions The BJP has called for boycotts, alleging privacy violations—despite their past positions—and portraying it as divisive politics. Internal conspiracies within the Congress, driven by dominant caste members, have led to “half-hearted” implementation, risking failure. As data digitization begins, the survey’s outcomes could influence upcoming elections and national debates on caste-based policies.

While the exercise promises data-driven equity, its critics warn of “socialism seeping in through bureaucracy.” As Karnataka processes the results, the nation watches whether this becomes a model for broader reforms or another shelved report.

The News Drill will continue monitoring developments in this evolving story.